With a new year upon us, many of us are deciding what old traditions and habits to throw out and what new commitments we will make to ourselves and others.

Full Story

With a new year upon us, many of us are deciding what old traditions and habits to throw out and what new commitments we will make to ourselves and others. 2020 was remarkable in that a maelstrom of problems coalesced. The COVID-19 pandemic shut down schools and teachers abruptly learned how to bring their teaching online. Students had to adjust to no longer seeing their classroom community and many of our most disadvantaged students are learning remotely despite city officials wanting to direct resources to reopening schools. Amidst the social isolation, the nation also saw the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the lack of accountability afterwards as a call to action. From anger and despair was a spark that forced conversations of race and equality into classrooms through computer screens; it laid bare our biases, privileges, and prejudices that we all hold. With the insurrection at the Capitol by white supremacists and rioters last week, the classroom becomes an essential place where conversations of fairness, justice, and police brutality happen. Now, the question is, after such an emotionally heavy year and tumultuous beginning to 2021, how will we move forward as teachers and what new commitments should we make for the future, not just in 2021?

I choose the word commitment, as opposed to resolution, because the word resolution is overused each new year and seems to connote individual resolve, as opposed to what I want to aim for, which is self and community commitment. These commitments are in the context for teachers, but since so many lives are touched by the work of teaching, learning, and educating our youth, it has a ripple effect on society. These commitments, I hope, can lead to broader social change. I highlight three big commitments that are important to me, as I, like so many of you, are on a learning journey to be a better teacher and person in 2021.

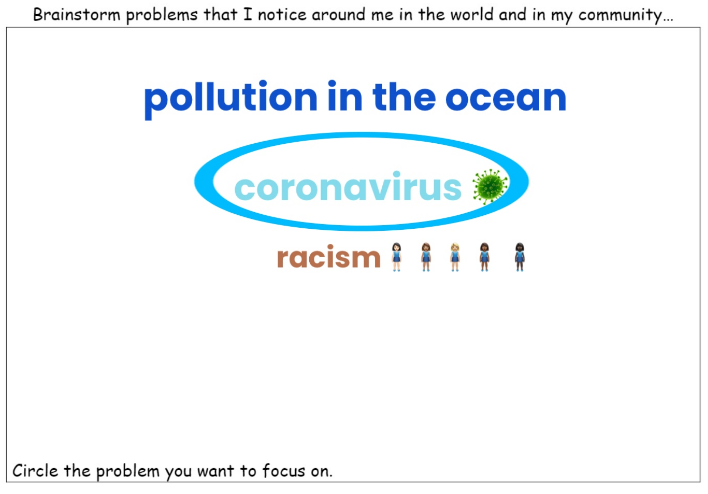

I commit to continue to integrate socially relevant issues into my curriculum and to help my students see their agency in this world. When I embarked on a new engineering design process project with my 2nd graders (7- and 8-year-olds), many of them saw COVID, pollution in the ocean, and racism as problems they wanted to tackle. (Left Photo: A 2nd-grade students’ work in their design engineering journal from Seesaw) Never too young, the students thought about problems they and their communities were facing and then designed something to help with the problem. They drew out their designs and then built prototypes out of recyclable materials while iterating on them with feedback from their peers in Zoom breakout rooms.

I commit to continue to integrate socially relevant issues into my curriculum and to help my students see their agency in this world. When I embarked on a new engineering design process project with my 2nd graders (7- and 8-year-olds), many of them saw COVID, pollution in the ocean, and racism as problems they wanted to tackle. (Left Photo: A 2nd-grade students’ work in their design engineering journal from Seesaw) Never too young, the students thought about problems they and their communities were facing and then designed something to help with the problem. They drew out their designs and then built prototypes out of recyclable materials while iterating on them with feedback from their peers in Zoom breakout rooms.It was one of my students’ favorite projects in which they were given free rein to think about any problem, any solution, and build anything they wanted to understand the engineering design process. Interestingly, this untethering from a teacher-defined problem that shifted the choice to the student was daunting for some. To others, they needed more time to think about a problem. Still, to some others, the engineering design process was an opportunity to think outside of the box and get creative on their third iteration. With every grade that completed the engineering design process project, the students sat with their initial discomfort and then gradually recognized that they are the changemakers, the inventors of technology for good. I recognized that in conceptualizing these lessons, the biggest barrier in bringing socially relevant issues into my curriculum was the unknowability of how your students (and families now sitting in on Zoom calls) will react. I’ve learned to embrace the surprise of the unknown and trust my instinct to honor student voices which will guide you through the difficult discourses that may emerge. Discussing privilege and race with elementary-aged students begins with an introspective look at yourself, though.

(Left Photo: A second grader’s first prototype, a mask holder. Right Photo: The same second grader’s final evolved prototype, a PPE Station, after getting feedback from her peers.)

I commit to remind myself of my roots to strive toward sharing my identity with my students. In front of my students a year ago, I wrote a poem about where I’m from. I recounted the distinct smells of fried dumplings with the savory smell of the steak wafting through my childhood home as I wrote the poem. I was reminded of my immigrant mother’s tired hands skilfully making the dumplings and marinating the steak. It was symbolic of my Chinese-American upbringing in Colorado. As I got to know my students, sharing stories about my experience and telling stories of not just any immigrant experience, but my family’s immigrant experience was how we built community, even virtually. My co-teacher, our grade colleagues, and I eventually turned it into an empathy interview activity where we had the students interview an adult to understand and facilitate conversation about difference. There were four questions they asked their adult: 1) Can you tell me about a time you felt different? 2) How did it make you feel? 3) Did you change from that moment? 4) What dreams do you have for me? In my role as the new STEM teacher, I integrate the empathy interview with my conversations around identity and belonging in computer science. This commitment to foster community and embrace difference is one that I want to sustain as a teacher.

I commit to my self-care and lifting up my fellow teachers in the profession. The most important commitment that I can make is to take care of myself so I can be there for my students and others. Teachers around the world are going above and beyond to engage students in virtual meetings where students may be dealing with trauma from the pandemic and the toll it’s taking on their families. Teachers are not immune either. Part of my commitment towards self-care is to recognize what I can balance and to say no to commitments I cannot manage. Additionally, collaborating and lifting up others is such a big part of a healthy school culture and for the teaching profession in general. With so many “day after” conversations teachers have had to have with their students around inciting or traumatic events, collaborating with your colleagues on how to discuss these events becomes important for our psyche and for our work as educators passionate about social justice. As we enter the new year, remember to take care of yourself and your colleagues.

Be patient with yourself and others; we are all on a learning journey. These commitments are not a sprint or a marathon. It is more a team relay where we try to achieve a better self, a better society together. When we pass on the baton and support each other, we can achieve something greater during these times of tumult. Let’s stick together and click refresh together.

About the Author

Shiela Lee is a special education teacher entering her 10th year of teaching. After spending a year teaching in Taiwan on a Fulbright Fellowship, she spent the next 8 years integrating computer science into her second-grade classroom in New York City. This upcoming year, she is the STEM teacher and is excited to help her students see their identities in the field of CS. Shiela is also a self-taught coder who has coded tools for teachers to use in their classroom, including a tool for stations teaching and an interactive hundreds chart to see mathematical patterns. She is committed to creating curriculum that is anti-racist and empowering her students to challenge stereotypes. Shiela is a Math for America Master Teacher Fellow and an Upperline Code Teaching Fellow. She holds a B.A. in philosophy from Grinnell College and a M.A. in curriculum and teaching from Teachers College, Columbia University.

Shiela Lee is a special education teacher entering her 10th year of teaching. After spending a year teaching in Taiwan on a Fulbright Fellowship, she spent the next 8 years integrating computer science into her second-grade classroom in New York City. This upcoming year, she is the STEM teacher and is excited to help her students see their identities in the field of CS. Shiela is also a self-taught coder who has coded tools for teachers to use in their classroom, including a tool for stations teaching and an interactive hundreds chart to see mathematical patterns. She is committed to creating curriculum that is anti-racist and empowering her students to challenge stereotypes. Shiela is a Math for America Master Teacher Fellow and an Upperline Code Teaching Fellow. She holds a B.A. in philosophy from Grinnell College and a M.A. in curriculum and teaching from Teachers College, Columbia University.