Full Story

-

Analytical thinking and innovation

-

Complex problem-solving

-

Critical thinking and Analysis

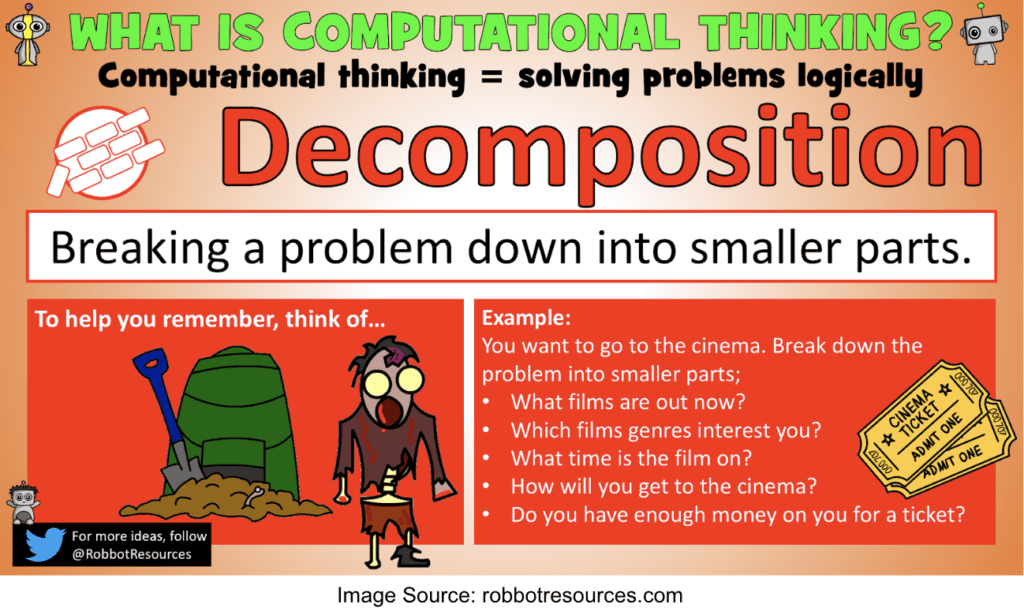

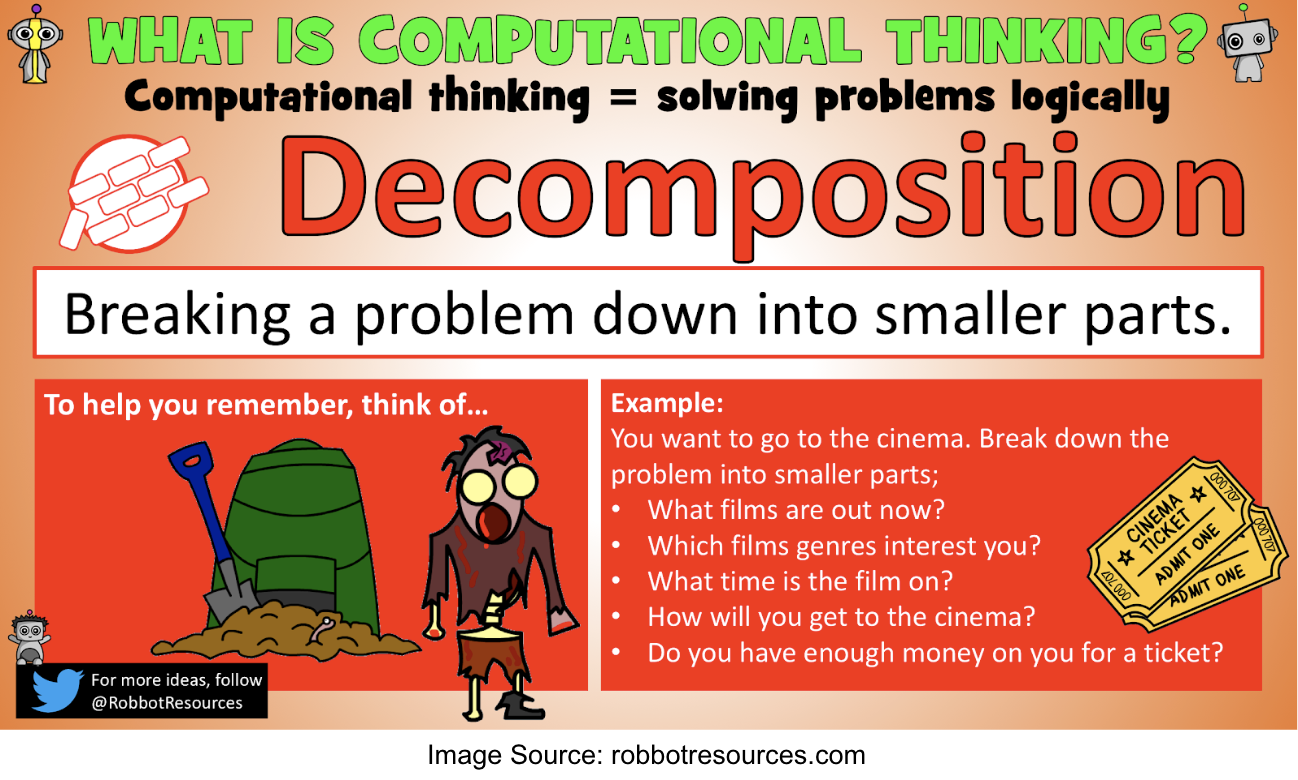

One of the first components of computational thinking is decomposition. What does this mean and how does it relate to school counselors? Every day your school counselors are demonstrating this skill to students. The concept of breaking down a problem into smaller parts is a crucial component of a student’s ability to address an area of concern. As counselors, this type of modification shows up in 504 planning and I&RS committee meetings as a strategy we can use to help a student grasp challenging content or behaviors. Modeling decomposition with students allows for the acquisition of this skill which places them in a position of advantage when obstacles arise whether it be on a school project, a computer program, or a situation at home. For example, if a student is having difficulty in a class, the counselor and student break the problem down and view it from different angles. Is the student studying regularly, taking advantage of extra help sessions, prepared for class (both academically with supplies and ready to learn – not hungry, tired), know where to find resources, etc.? Breaking down the problem and considering a variety of possible contributing factors is the essence of decomposition.

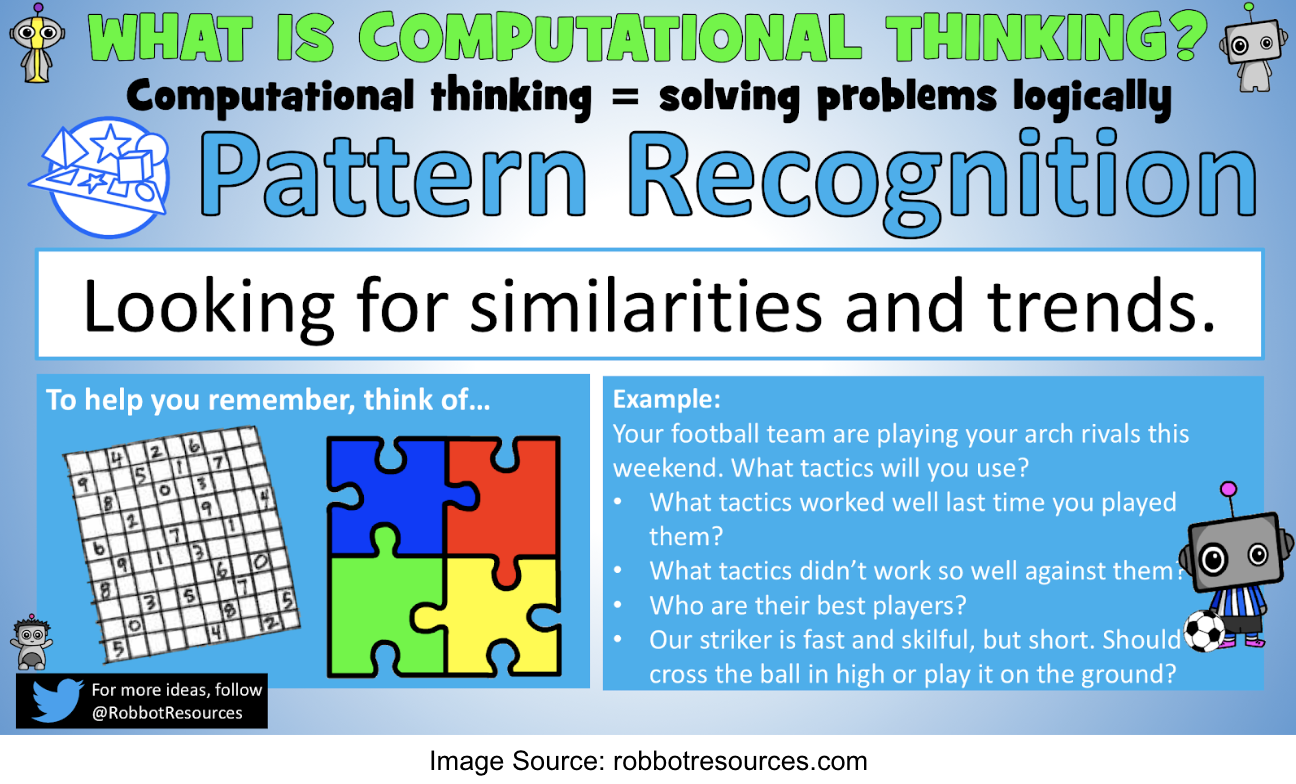

One of the first components of computational thinking is decomposition. What does this mean and how does it relate to school counselors? Every day your school counselors are demonstrating this skill to students. The concept of breaking down a problem into smaller parts is a crucial component of a student’s ability to address an area of concern. As counselors, this type of modification shows up in 504 planning and I&RS committee meetings as a strategy we can use to help a student grasp challenging content or behaviors. Modeling decomposition with students allows for the acquisition of this skill which places them in a position of advantage when obstacles arise whether it be on a school project, a computer program, or a situation at home. For example, if a student is having difficulty in a class, the counselor and student break the problem down and view it from different angles. Is the student studying regularly, taking advantage of extra help sessions, prepared for class (both academically with supplies and ready to learn – not hungry, tired), know where to find resources, etc.? Breaking down the problem and considering a variety of possible contributing factors is the essence of decomposition.  During pattern recognition in computational thinking, students learn to recognize trends and similarities. What worked successfully last time they ran into this problem? What didn’t work? If students have run into this problem before, what did they learn that worked well or didn’t work that they can apply to this situation? In the scenario of a student struggling in a class, the student and counselor might reflect on how the student performed in this subject area the previous year. Is this possibly a new area of study in which the student lacks enough background experience? A counselor might meet with the students’ peers in the class to learn about their study habits, resources they use, and other strategies they employ. Identifying patterns of what has worked and not worked in the past along with identifying patterns of behavior in students who are doing well in the class provides a framework to create a collaborative plan for the struggling student. It also models a problem-solving strategy they can apply to other situations to support more positive outcomes.

During pattern recognition in computational thinking, students learn to recognize trends and similarities. What worked successfully last time they ran into this problem? What didn’t work? If students have run into this problem before, what did they learn that worked well or didn’t work that they can apply to this situation? In the scenario of a student struggling in a class, the student and counselor might reflect on how the student performed in this subject area the previous year. Is this possibly a new area of study in which the student lacks enough background experience? A counselor might meet with the students’ peers in the class to learn about their study habits, resources they use, and other strategies they employ. Identifying patterns of what has worked and not worked in the past along with identifying patterns of behavior in students who are doing well in the class provides a framework to create a collaborative plan for the struggling student. It also models a problem-solving strategy they can apply to other situations to support more positive outcomes.

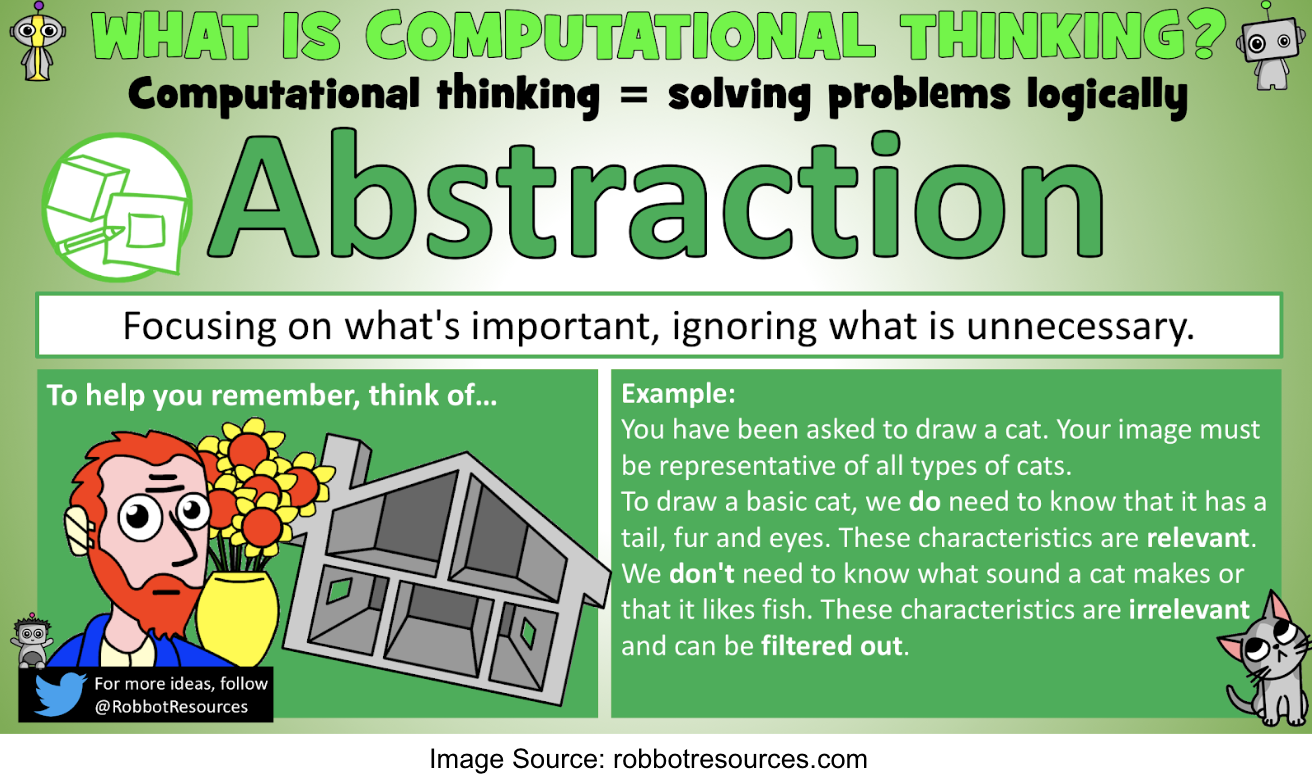

Abstraction is about focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem and not getting distracted by the red herrings. Rarely do students come to a school counselor with a clear, concise statement about the problem or view of a situation. Often there is a great deal of extra information that feels critical to the student. By taking a step back, counselors can help students focus on what is truly relevant to the problem. This challenge of sorting through details and distractions isn’t a problem relegated to children; it’s a human problem! We all struggle with this from time to time. Think of the last time you were late to work. You might have run through a list of frustrations that led to you being late, and some might have been legitimate problems to address (the alarm didn’t go off) while others might be annoying situational frustrations that may not relate to being late (Why does the dog always take so long to go to the bathroom on cold mornings?). Being able to tease out what is truly necessary to consider when solving a problem is not just a computational thinking skill, but it is also a critical life skill! School counselors view this as “stripping away the drama and pulling out the facts.” The key is to identify which aspects are truly relevant to solving the problem.

Abstraction is about focusing on the most relevant aspects of a problem and not getting distracted by the red herrings. Rarely do students come to a school counselor with a clear, concise statement about the problem or view of a situation. Often there is a great deal of extra information that feels critical to the student. By taking a step back, counselors can help students focus on what is truly relevant to the problem. This challenge of sorting through details and distractions isn’t a problem relegated to children; it’s a human problem! We all struggle with this from time to time. Think of the last time you were late to work. You might have run through a list of frustrations that led to you being late, and some might have been legitimate problems to address (the alarm didn’t go off) while others might be annoying situational frustrations that may not relate to being late (Why does the dog always take so long to go to the bathroom on cold mornings?). Being able to tease out what is truly necessary to consider when solving a problem is not just a computational thinking skill, but it is also a critical life skill! School counselors view this as “stripping away the drama and pulling out the facts.” The key is to identify which aspects are truly relevant to solving the problem.

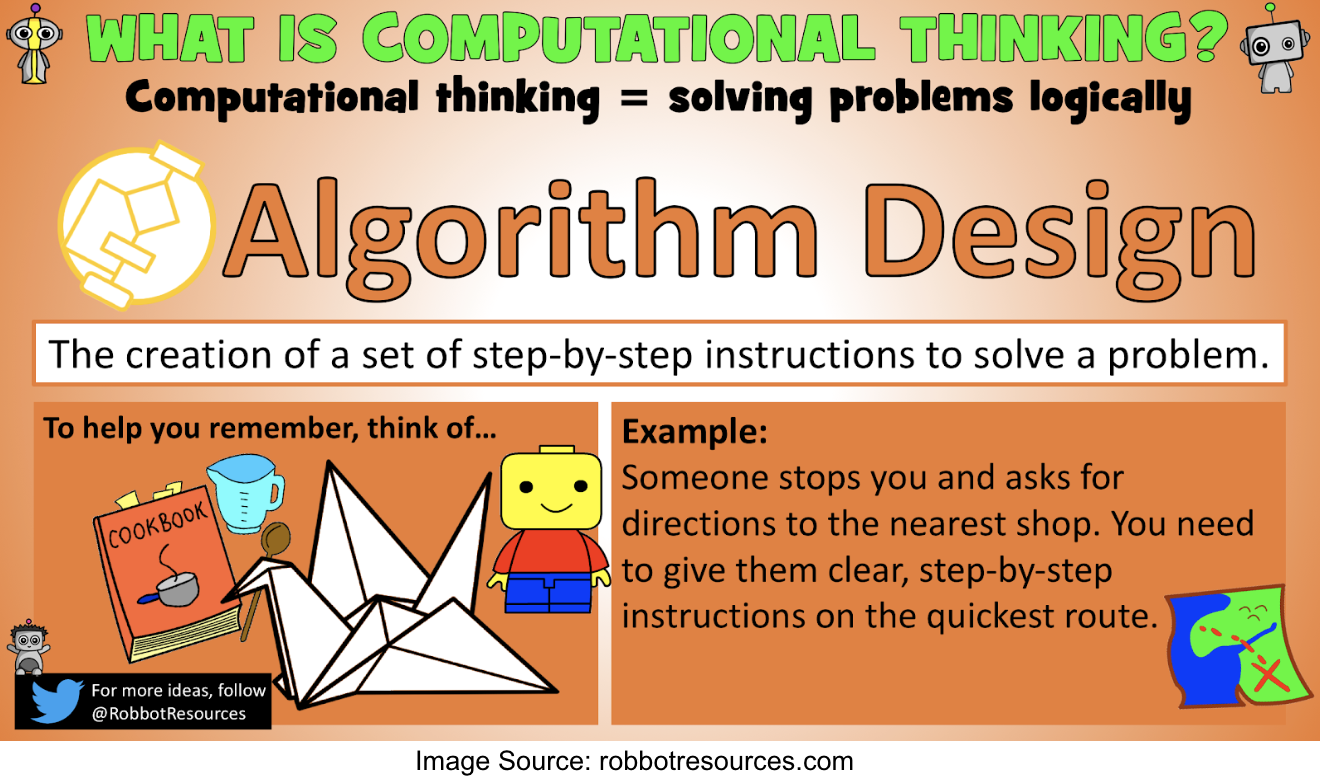

Computational thinking also encompasses algorithm design, which is a step-by-step process for solving problems. Think of an algorithm as being like a recipe: very specific, measured ingredients combined in a clearly defined order. When counselors work with students on challenges, they develop a plan that involves a step-by-step process for addressing the obstacle and “debugging” or anticipating challenges and problem-solving. Within the creation of the plan, they need to provide for anticipated roadblocks. How might that student address anticipated challenges? For example, a counselor might verbally “walk through” the student’s process of leaving period 1 class to arrive in period 2 class on time. Does the student stay behind and chat with the teacher or peers? Does the student circle back to the locker to pick up supplies or take a longer than necessary route to the next class? Creating a step-by-step “recipe” to get to class on time is a transferable skill for other life challenges.

Computational thinking also encompasses algorithm design, which is a step-by-step process for solving problems. Think of an algorithm as being like a recipe: very specific, measured ingredients combined in a clearly defined order. When counselors work with students on challenges, they develop a plan that involves a step-by-step process for addressing the obstacle and “debugging” or anticipating challenges and problem-solving. Within the creation of the plan, they need to provide for anticipated roadblocks. How might that student address anticipated challenges? For example, a counselor might verbally “walk through” the student’s process of leaving period 1 class to arrive in period 2 class on time. Does the student stay behind and chat with the teacher or peers? Does the student circle back to the locker to pick up supplies or take a longer than necessary route to the next class? Creating a step-by-step “recipe” to get to class on time is a transferable skill for other life challenges.