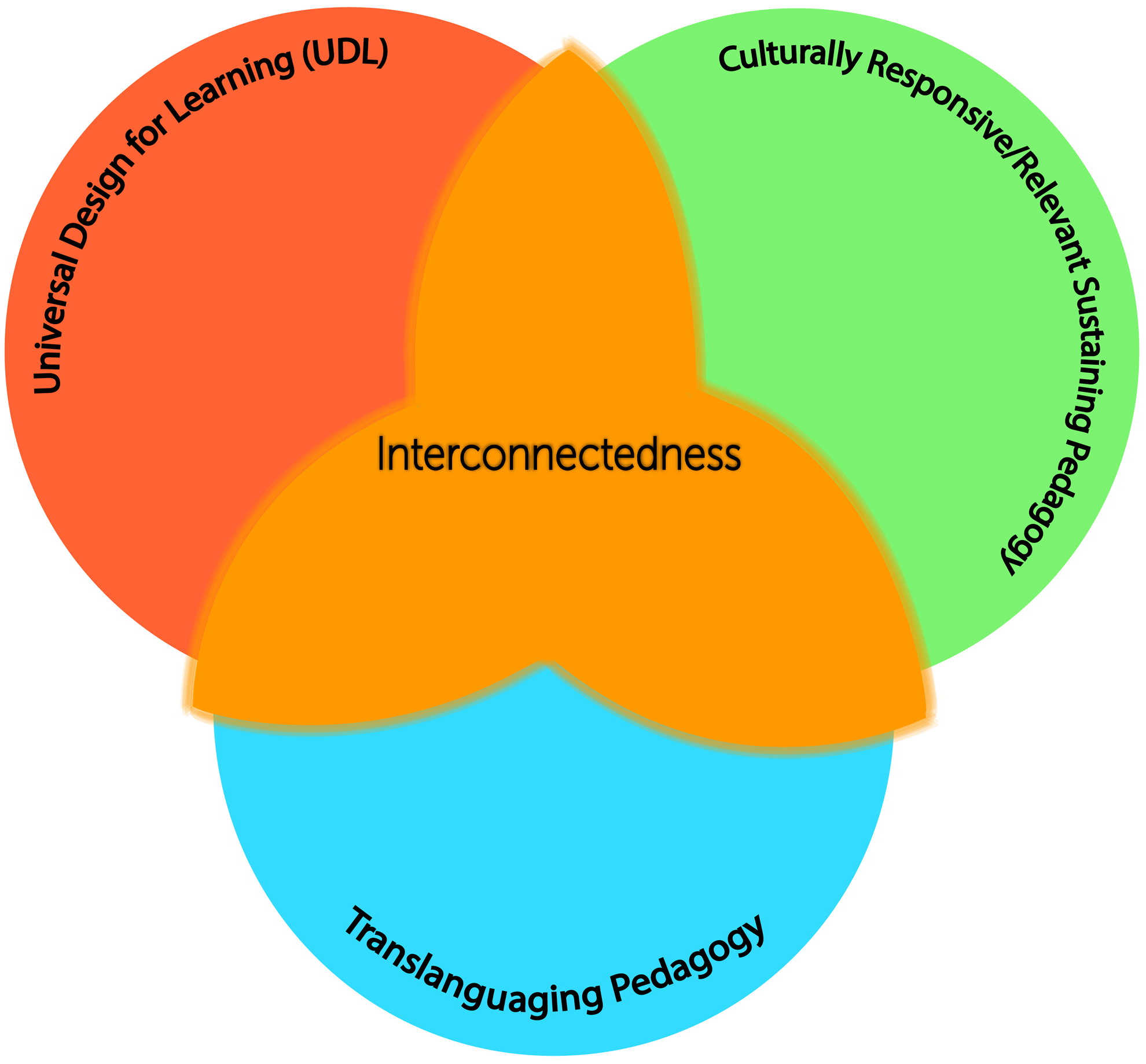

Inclusive teaching involves three interrelated pedagogies:

Inclusive teaching involves three interrelated pedagogies:

- culturally responsive / relevant pedagogy (CRP): a pedagogical framework that appreciates, integrates, and prioritizes the lived experiences of diverse identity groups (racial, ethnic, ability, and sexual orientation) within the context of teaching and learning

- translanguaging: a theory from bilingual education that describes what people (but especially bi/multilinguals) do when they use all of their language and communication resources to make meaning, learn, and express themselves

- universal design for learning (UDL): an instructional planning approach designed to give all students an equal opportunity to learn by removing barriers that prevent students from fully engaging in their classroom communities

Learn more about these pedagogies by expanding the sections below.

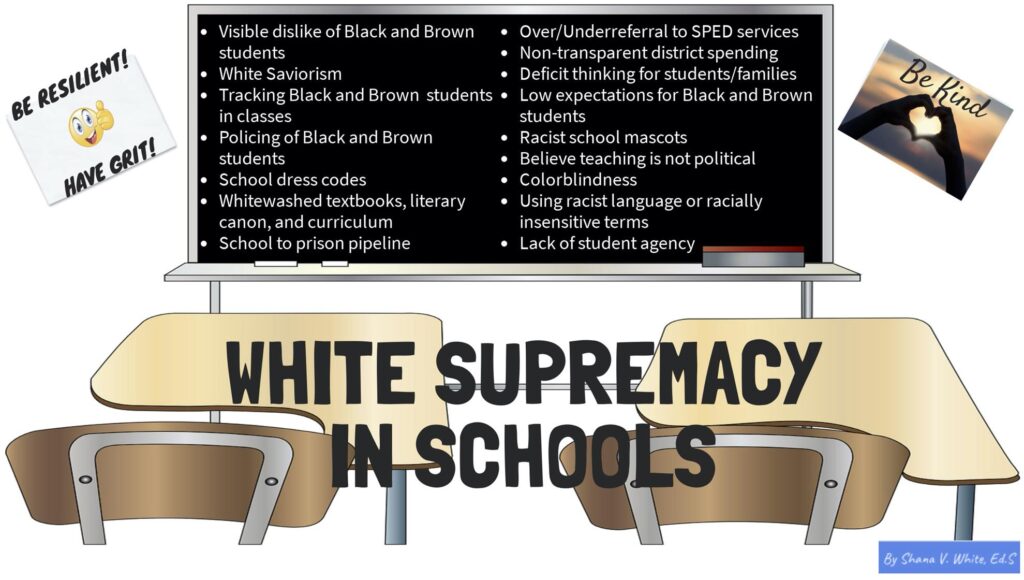

Culturally Relevant/Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) is a pedagogical framework that appreciates, integrates, and prioritizes the lived experiences of diverse identity groups (racial, ethnic, ability, and sexual orientation) within the context of teaching and learning. CRP is based on the understanding that the curriculum currently utilized in our school both pedagogically and instructionally centers whiteness and other normative identities including spoken language, content-based texts, gender, sexuality, historical contexts, and classroom norms. This is a missed opportunity to draw on the cultural capital of students of color and dehumanizes them and their lived experiences in a school environment. Humanizing pedagogy is the process of moving students from self-hate to self-love, moving to political solidarity, and sub-oppression to self-determination. (Humanizing Education) Teachers implementing CRP are committed to the process of becoming culturally aware, anti-racist, LGBTQ+ affirming, and ethnically inclusive in their thinking with a thorough understanding of hierarchies, power, and social and economic inequities in schools and society at large.

- Asset-Based Perspective: A transformational perspective that recognizes and values the rich cultural practices embedded in all communities.

- Deficit-Based Perspective: Implies that students are flawed or deficient and that the role of the school is to fix the student. Deficit-based teaching seeks to teach to students’ weaknesses instead of teaching to their strengths.

- Diversity: A reality created by individuals and groups from a broad spectrum of demographic and philosophical differences. These differences can exist along dimensions of race, ethnicity, gender, language heritage, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs, or other ideologies.

- Equity: The state, quality, or ideal of being just, impartial, and fair. The concept of equity is synonymous with fairness and justice. To be achieved and sustained, equity needs to be thought of as a structural and systemic concept, and not as idealistic.

- Gender: A non-binary association of characteristics within the broad spectrum between masculinities and femininities.

- Inclusive: More than simply diversity and numerical representation, being inclusive involves authentic and empowered participation and a true sense of belonging by all identities and individual groups.

- Internalized Racism: Describes the private racial beliefs held by and within individuals that run in sync and are derived from white supremacy.

- Interpersonal Racism: Describes how our private beliefs about race become public when we interact with other people.

- Institutional Racism: Describes the racial inequity baked into our institutions, connoting a system of power that produces racial disparities in domains such as law, health, employment, education, and so on. It can take the form of unfair policies and practices, discriminatory treatment, and inequitable opportunities and outcomes.

- Microaggressions: The everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership.

- Pluralism: A socially constructed system in which members of an identity group maintain participation in this group even as they belong to a larger cultural group. Educational pluralism is when students can leverage aspects of their cultural background as assets for learning and sustain those assets throughout their schooling.

- Race: A socially constructed system of categorizing humans largely based on observable physical features (phenotypes) such as skin color and ancestry. There is no scientific basis for or discernible distinction between racial categories.¹

- Racial Justice: The systematic fair treatment of people of all races that results in equitable opportunities and outcomes for everyone. All people are able to achieve their full potential in life, regardless of race, ethnicity, or the community in which they live. Racial justice — or racial equity —goes beyond “anti-racism.” It’s not just about what we are against, but also what we are for.

- Racial Literacy: The ability and practice of reading (awareness), recasting (stress management), and resolving (challenging and advocating) racially stressful encounters through the use of behavioral techniques including journaling, role-play, and debate.

- Socio-Political Consciousness: An awareness of both the social and political factors at play in the workings of complex societal systems. This consciousness is necessary for navigating complex systems based on a unity of thought and performance, reflective practice and deliberative action, skills that are meaningful, and necessary for participation in expanding global economies and democracies.

- Structural Racism: The operation of racial bias across institutions and society. It describes the cumulative and compounding effects of an array of factors that systematically privilege one group over another.

- Systematic Equity: A complex combination of interrelated elements and actions designed to create, support, and sustain social justice. It is a robust system and dynamic process that reinforces and replicates equitable ideas, power, resources, strategies, conditions, habits, and outcomes.

- Systemic Racialization: The operation of racial bias across institutions and society. It describes the cumulative and compounding effects of an array of factors that systematically privilege one group over another.

- Systematic Racism: The understanding that the outcomes or results of the system would harm certain BIPOC more harshly no matter who is in charge. It is the understanding that the entire system is determined by race-based factors, the system upholds racist policies/decisions, and the system cannot be reformed in order to adequately and properly meet the needs of all individuals.

- Whiteness: The concept that stems from white supremacy that sets certain identity characteristics as the default or norm. Whiteness believes white cis-heterosexual, able-bodied, neurotypical, Christian, males are deemed central and considered normal, and all other identities are naturally marginalized and decentered.

- White privilege: The benefits, entitlement, and advantages that one gets for being identified as a member of the white race.

- White saviorism: It is the self-serving belief a person from the white race must save people of color from schools, situations, environments, and society at large without actually shifting and leveraging the power they have in those situations.

- White supremacy: The hierarchy and power structure that is based on the social construction of race which places members of the “white” race at the top of the hierarchy structure, providing them with the most power, and thus places other socially constructed racial groups (Black, Native Peoples, Asian, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander) below them.

The majority of these definitions are from the New York State Education Department’s Culturally Responsive – Sustaining Education Framework (2020).

How white supremacy culture manifests in schools and classrooms:

- Cianciotto, J., & Cahill, S. (2012). LGBT youth in America’s schools. University of Michigan Press.

- Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gay, G., & Howard, T. C. (2000). Multicultural teacher education for the 21st century. The Teacher Educator, 36(1), 1–16.

- Gay, G. (2002). Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. Journal of teacher education, 53(2), 106-116.

- Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Jacob, S. (2013). Creating safe and welcoming schools for LGBT students: Ethical and legal issues. Journal of School Violence, 12(1), 98-115.

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465-491.

- Ladson‐Billings, G. (1995) But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy, Theory Into Practice, 34(3), 159-165,

- McInnes, Brian D. (2017) Preparing teachers as allies in Indigenous education: benefits of an American Indian content and pedagogy course, Teaching Education, 28(2), 145-161.

- Nieto, S. (2013). Finding joy in teaching students of diverse backgrounds: Culturally responsive and socially just practices in U.S. classrooms. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Reyhner, J., & Jacobs, D. T. (2002). Preparing teachers of American Indian and Alaska Native students. Action in Teacher Education, 24, 85–93.

- Reyhner, J., Lee, H., & Gabbard, D. (1993). A specialized knowledge base for teaching American Indian and Alaska Native students. Tribal College Journal, 4, 26–32.

- Russell, S. T., & McGuire, J. K. (2008). The school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) students. Toward positive youth development: Transforming schools and community programs, 133-149.

- Savage, C., Hindle, R., Meyer, L. H., Hynds, A., Penetito, W., & Sleeter, C. E. (2011). Culturally responsive pedagogies in the classroom: Indigenous student experiences across the curriculum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 39, 183–198.

- Ware, F. (2006). Warm demander pedagogy: Culturally responsive teaching that supports a culture of achievement for African American students. Urban Education, 41(4), 427-456.

What and how US schools teach tends to emphasize the dominant language — English — and white middle-class culture. For this reason, bi/multilingual students — students who use language(s) other than English are often labeled by school systems as “English Language Learners.” But that label is deficit-based, focusing on the object of students’ learning, and not who they are: bi/multilingual people with rich language and communication practices that go far beyond English. In recent years, many have re-framed the way schools think about educating these students (Garcia & Kleifgen, 2010; 2018) — with some using the asset-based term “bi/multilingual students or learners” to refer to them.

The concept of translanguaging aims to counter deficit ways of viewing students’ language practices. It is a theory from bilingual education that describes what people (but especially bi/multilinguals) do when they use ALL of their language and communication resources to make meaning, learn, and express themselves (García & Li Wei, 2014). Those resources include oral and written varieties of different languages, slang, body language, drawing, gesture, and even what people do with technology to communicate. Translanguaging views language as fluid and dynamic. As stated in PiLaCS (2020):

Traditional linguists, and even some teachers, might hear students talk, or read their writing, and think that students are “breaking the rules” of language. But translanguaging promotes another view — it asks us to think critically about the rules themselves. Who gets to determine what the “standard language” is? How have these standards harmed our students?

Translanguaging pedagogy (Creese & Blackledge, 2010; García et al., 2017; García & Kleyn, 2016) is an evidence-based approach rooted in the idea that students learn best when they can leverage all of their language resources. Research shows that students from all language backgrounds can succeed with the right support and resources, including bi/multilingual resources and program models (Collier & Thomas, 2017). Translanguaging pedagogy was developed by educators working with bi/multilingual students, though its core tenet about welcoming all the ways students communicate is relevant to work with all student populations. It can be implemented by any educator, regardless of their experience with more than one language.

To implement translanguaging pedagogy, teachers should consider three components of their teaching (García et al., 2017):

- Take up a stance that centers how bi/multilingual students communicate. Educators who practice translanguaging pedagogy learn about their students’ diverse language practices. They do not restrict students to standard English, instead welcoming students to translanguage to make sense, learn, and express. They prompt students to think critically about when, how, and why to use different types of language at different times. They also help students expand their language repertoires to include ways of speaking and interacting valued in a range of computing communities (see Jacob et al., 2018).

- Design units, classroom environments, and digital learning spaces to intentionally leverage students’ diverse language practices for learning. Computer science teachers include students’ languages and ways of expression in class materials (like slides and handouts) as well as around classrooms, school hallways, and digital learning spaces, creating a “multilingual ecology” (García et al., 2017). Teachers might select programming environments that are available in multiple languages (e.g. Scratch). When those are not available, teachers develop or help students develop multilingual or multimodal representations and documentation of code and CS concepts. They build on bi/multilingual learners’ translanguaging to help them develop programming and computational thinking skills. In line with CRSE approaches, translanguaging unit and lesson plans might also engage students in using code along with different language and communication resources to take action and participate in their worlds (Vogel et al., 2020).

- Make in the-moment shifts to adapt their practice to students’ dynamic language practices. Given that students’ language practices are dynamic, teachers should be ready to change up their teaching in the moment to help students make meaning. For instance, if a student is unclear about a question you are asking, you might try posing it another way using machine translation software or an image on the electronic whiteboard, or ask classmates to try putting the question into other words.

- Participating in Literacies and Computer Science – Offers up an approach for supporting bi/multilingual learners in computer science education, as well as resources for educators to plan computer science-integrated units that leverage students’ translanguaging as a resource.

- City University of New York – New York State Initiative on Emergent Bilinguals – General (non-CS) resources to learn more about and apply translanguaging in your classroom. Includes strategy guides, video and written case studies from classrooms across subject areas.

- IMPACT-CONECTAR – Leverages a culturally relevant approach and focuses on language learning for multilingual students. It offers a 4th grade, Scratch-based curriculum and recommended supplementary resources.

- Bi/multilingual learner: Students who speak one or more languages other than English and who are learning English. Although federal policy documentation still uses the term English Language Learner, many states are moving towards more asset-based terms like this one.

- Translanguaging pedagogy: When teachers take up a stance that centers how bi/multilingual students communicate, when they design their units and classroom environment to intentionally leverage students’ diverse language practices for learning, when they make in the-moment shifts to adapt their practice to students’ dynamic language abilities (García et al., 2017).

- Translanguaging: Translanguaging is a theory from bilingual education that describes what people (but especially bi/multilinguals) do when they use all of their language and communication resources to make meaning, learn, and express themselves (García & Li Wei, 2014). Those resources include oral and written varieties of different languages, slang, body language, drawing, gesture, and even what people do with technology to communicate.

- Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2017). Validating the Power of Bilingual Schooling: Thirty-Two Years of Large-Scale, Longitudinal Research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190517000034

- Creese, A., & Blackledge, A. (2010). Translanguaging in the bilingual classroom: A pedagogy for learning and teaching? The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 103–115.

- García, O., Ibarra Johnson, S., & Seltzer, K. (2017). The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning. Caslon Publishing.

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2010). Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Language Learners (1st edition). Teachers College Press.

- García, O., & Kleifgen, J. A. (2018). Educating Emergent Bilinguals: Policies, Programs, and Practices for English Language Learners (2nd Edition). Teachers College Press.

- García, O., & Kleyn, T. (Eds.). (2016). Translanguaging with Multilingual Students: Learning from Classroom Moments. Routledge.

- García, O., & Li Wei. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan Pivot.

- Jacob, S., Nguyen, H., Tofel-Grehl, C., Richardson, D., & Warschauer, M. (2018). Teaching Computational Thinking To English Learners. NYS TESOL Journal, 5(2). http://journal.nystesol.org/july2018/4Jacob%28CGFP%29.pdf

- Participating in Literacies and Computer Science. (Forthcoming). Introducing Translanguaging for Computer Science Educators. www.pila-cs.org

- Vogel, S., Hoadley, C., Castillo, A. R., & Ascenzi-Moreno, L. (2020). Languages, literacies, and literate programming: Can we use the latest theories on how bilingual people learn to help us teach computational literacies? Computer Science Education. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08993408.2020.1751525

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is an instructional planning approach designed to give all students an equal opportunity to learn by removing barriers that prevent students from fully engaging in their classroom communities. Teachers who plan through the UDL framework assume that learner variability, including (dis)Ability, is a given in all classrooms and that differences between learners is an asset. Thus, rather than creating lesson plans aimed at the “average” learner, and then modifying those lessons for “other” learners that cannot access that lesson, they design instruction in a flexible manner so all students can engage in learning as part of the classroom community. When developing lessons and assessments through the UDL framework, teachers consider three broad UDL principles: (1) Engaging learners and making learning personally relevant to all learners; (2) Presenting content in multiple ways that allows students to learn content through different formats, and (3) Providing flexible ways for students to interact with instructional content and demonstrate their understanding of that content in a way that leverages their strengths rather than amplifying any challenges. Each of these principles are broken down into guidelines that provide further detail about implementing these three principles. Lastly, there is no single way to teach through the UDL framework because teachers use the UDL guidelines in response to the needs of their learners.

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL) + Computer Science/Computational Thinking examples

- CAST: The UDL Guidelines

- CAST: UDL Resources and Tips

- Understood.org: What is Universal Design for Learning (UDL)?

- Creative Technology Resource Lab: Teaching All Computational Thinking through Inclusion and Collaboration (TACTIC)

- AccessCSforAll: The UDL Guidelines

(dis)Ability: Our approach to (dis)ability considers systemic barriers, inaccessibility in curriculum and tools, biases, lack of effective pedagogical knowledge and social exclusion will result in the disabling of students rather than something internal to them. All students come into the classroom with a set of strengths, challenges, motivations, and backgrounds. These differences should be celebrated rather than seen through a deficit perspective.

Creators

Shana V. White, Meg Ray, Maya Israel, Michelle G. Lee, Christy Crawford, Sara Vogel, Francisco Cervantes, Elizabeth Bishop, and Todd Lash

CSTA’s thinking about how to best support bi/multilingual students in CS education has been informed by and borrows from the work of the Participating in Literacies and Computer Science (PiLa-CS) research practice partnership, led by Christopher Hoadley, Laura Ascenzi-Moreno, Jasmine Ma, Kate Menken, Sara Vogel, Marcos Ynoa, and Sarah Radke.